The provisions of the AI Act on prohibited AI practices (Article 5 of the AI Act) will become applicable quite quickly, 6 months after the entry into force of the AI Act (i.e. from February 2, 2025).

As discussed in a previous post, the AI Act takes a risk-based approach and accordingly, we can distinguish AI practices that should be prohibited due to unacceptably high risks (prohibited AI practices, Article 5 of the AI Act, e.g. social scoring systems), high-risk AI systems that require strict requirements and compliance with a number of obligations set out in the AI Act (high-risk AI systems, Article 6 of the AI Act) and other lower-risk AI systems that are essentially subject to transparency obligations (Article 50 of the AI Act, e.g. chatbots). (There are additional AI systems with minimal risk for which no additional requirements are essentially laid down in the regulation. This category could include, for example, spam filters.)

In the following, I will take a closer look at the so-called prohibited AI practices deined in the AI Act.

1. What prohibited AI practices are listed in the AI Act?

The AI Act classifies the following practices as prohibited AI practices involving an unacceptably high risk:

- AI systems using subliminal or purposefully manipulative or deceptive techniques,

- AI system that exploits vulnerabilities of a person or a specific group of persons,

- Social scoring systems,

- AI systems intended for risk assessment regarding the likelihood of crime,

- Facial recognition databases,

- Emotion recognition in the areas of workplace and education institutions,

- Biometric categorisation systems,

- ‘Real-time’ remote biometric identification systems in publicly accessible spaces for the purposes of law enforcement.

2. What should you know about the prohibited AI practices?

Below, I will review each prohibited AI practice and show (i) what techniques and methods, (ii) what objectives or effects, and (iii) what consequences and outcomes may lead to the establishment of an unacceptably high-risk practice. For certain practices where the AI Act provides for this, I will also present exceptions to the prohibitions. As we will see, the prohibitions apply to the placing on the market, putting into service or use of specific AI systems. These terms are defined in the AI Act as follows:

- placing on the market: the first making available of an AI system or a general-purpose AI model on the Union market (Art. 3, Point 9),

- putting into service: the supply of an AI system for first use directly to the deployer or for own use in the Union for its intended purpose* (Art. 3, Point 11), [*"intended purpose means the use for which an AI system is intended by the provider, including the specific context and conditions of use, as specified in the information supplied by the provider in the instructions for use, promotional or sales materials and statements, as well as in the technical documentation", Art. 3., Point 12]

- use: there is no specific definition in this regard in the AI Act. The "use" is mainly manifested through the concept of "deployer" ("deployer means a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body using an AI system under its authority except where the AI system is used in the course of a personal non-professional activity", see Art. 3, Point 4)

2.1 AI systems using subliminal or purposefully manipulative or deceptive techniques [Art. 5 (1) a)]

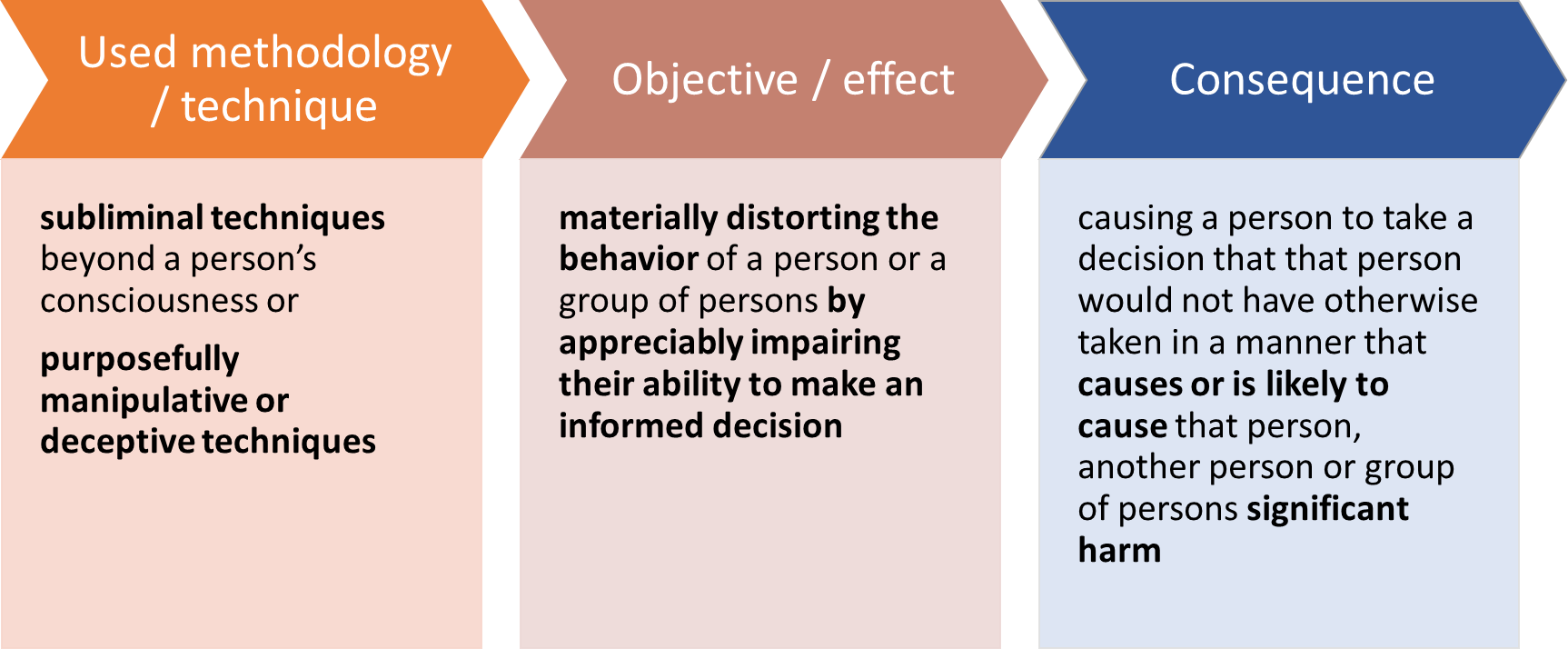

The placing on the market, the putting into service or the use of an AI system that deploys

- subliminal techniques beyond a person’s consciousness or

- purposefully manipulative or deceptive techniques,

with the objective, or the effect of materially distorting the behaviour of a person or a group of persons by appreciably impairing their ability to make an informed decision,

thereby causing them to take a decision that they would not have otherwise taken in a manner that causes or is reasonably likely to cause that person, another person or group of persons significant harm

shall be prohibited.

What can be subliminal or manipulative techniques prohibited by the AI Act?

This could mean the use of subliminal components (e.g. sound, visual and video stimuli) that persons are unable to perceive because those stimuli go beyond human perception, or the use of manipulative or deceptive techniques that undermine or impair a person's autonomy, decision-making or free choice without human awareness of it, or, even if they are aware of it, they are deceived by the use of that technique or are unable to control or resist it. Howeverr, common and legitimate commercial practices, for example in the field of advertising, that comply with the applicable law should not, in themselves, be regarded as constituting harmful manipulative AI-enabled practices (see Recital 29).

Questions concerning subliminal messages and their impact have occupied scientists and the wider public for decades. In connection with advertising, the effect of subconscious messages (not consciously perceptible to the recipient) is discussed. The topic has been on the agenda since the 50s, after a market researcher named James Vicary claimed that thanks to subliminal messages hidden in a movie, he was able to significantly increase viewers' consumption of Coke and popcorn. Later, it was disputed that the announcement was based on solid scientific research, and that experiments since then do not necessarily prove the convincing effect of subliminal advertising. However, the genie has been let out of the bottle and several bans have been imposed on the use of such techniques for advertising purposes (e.g. in the EU, the so-called "Audiovisual Media Services Directive" contains a ban on "unconscious techniques", the Council of Europe's European Convention on Transfrontier Television (1989) prohibits the use of subliminal techniques in Article 13(2); nor is the use of these techniques for advertising purposes permitted in the USA).

However, the real or perceived impact of subliminal messages can manifest itself in ways far more dangerous than incomplete consumer decisions. In 1990, for example, the band Judas Priest was prosecuted on the grounds that the subliminal messages used in their songs led to two young people ending their lives by their own hands. In the end, the court did not find the band responsible for the suicide of the youths.

(For a legal assessment of subliminal messages, please see, for example, Salpeter-Swirsky's study, "Historical and Legal Implications of Subliminal Messaging in the Multimedia: Unconscious Subjects" Nova Law Review, 2012, Volume 36, Issue 3.)

In connection with the definition of subliminal techniques, it is worth reading Zhong. et al "Regulating AI: Applying Insights from Behavioural Economics and Psychology to the Application of Article 5 of the EU AI Act", which presents several possible techniques. Franklin et al.'s "Strengthening the EU AI Act: Defining Key Terms on AI Manipulation" may help define subliminal, manipulative and deceptive techniques in relation to the AI Act. Bermúdez et. al.: "What Is a Subliminal Technique? An Ethical Perspective on AI-Driven Influence" is also a useful reading, which discusses the ethical implications of subconscious influence in the context of AI. Based on the narrow interpretation of the concept and its practical problems, a broader definition is proposed in the study, which may provide adequate protection in relation to individual freedom of decision. The authors of the study propose the use of a broader definition in AI development and offer a decision tree that could be used to filter out prohibited practices in this area.

The use of so-called 'dark patterns' in connection with manipulative and deceptive techniques has been in the spotlight for some time and has been the subject of numerous analyses, including from a data protection and consumer protection point of view. (See, for example, the relevant factsheet from the Finnish Competition and Consumer Protection Authority, while for the data protection aspects of dark patterns, see EDPB´s guidance on deceptive patterns in social media, "Guidelines 03/2022 on Deceptive design patterns in social media platform interfaces: how to recognise and avoid them".)

What can be considered as "appreciably impairing ability to make an informed decision" that could lead to materially biased behaviour?

In practice, in connection with the appreciably impairing of decision-making capacity or the materially biased behavior, the question arises as to where these boundaries can be drawn, what does "appreciably imparing" mean and what can be regarded as "material bias". It is currently difficult to give an unequivocal answer to this, but it is likely that the nature and extent of the possible consequence (harm) (see below) will be used to judge whether the interference with decision-making capacity or behaviour may have been appreciable or material. The technique used to influence the decision-making ability can also be a relevant factor. The more serious the intervention (whether physical, e.g. through interfaces, or virtually, e.g. in virtual reality), the more likely it is that significant influence may materialize.

According to the Recital to the AI Act, weakening the ability to make informed decisions, "could be facilitated, for example, by machine-brain interfaces or virtual reality as they allow for a higher degree of control of what stimuli are presented to persons, insofar as they may materially distort their behaviour in a significantly harmful manner." (See Recital 29, emphasis added.)

What significant harm does or reasonably likely to be caused by the use of these techniques?

Significant harm may include, in particular, "sufficiently important adverse impacts on physical, psychological, health or financial interests". It also includes "harms that may be accumulated over time" (see Recital 29). Based on the Recital to the AI Act (see Recital 29, emphasis added), it is also important to underline that

[...] it is not necessary for the provider or the deployer to have the intention to cause significant harm, provided that such harm results from the manipulative or exploitative AI-enabled practices.

2.2 AI system that exploits vulnerabilities of a person or a specific group of persons [Art. 5 (1) b)]

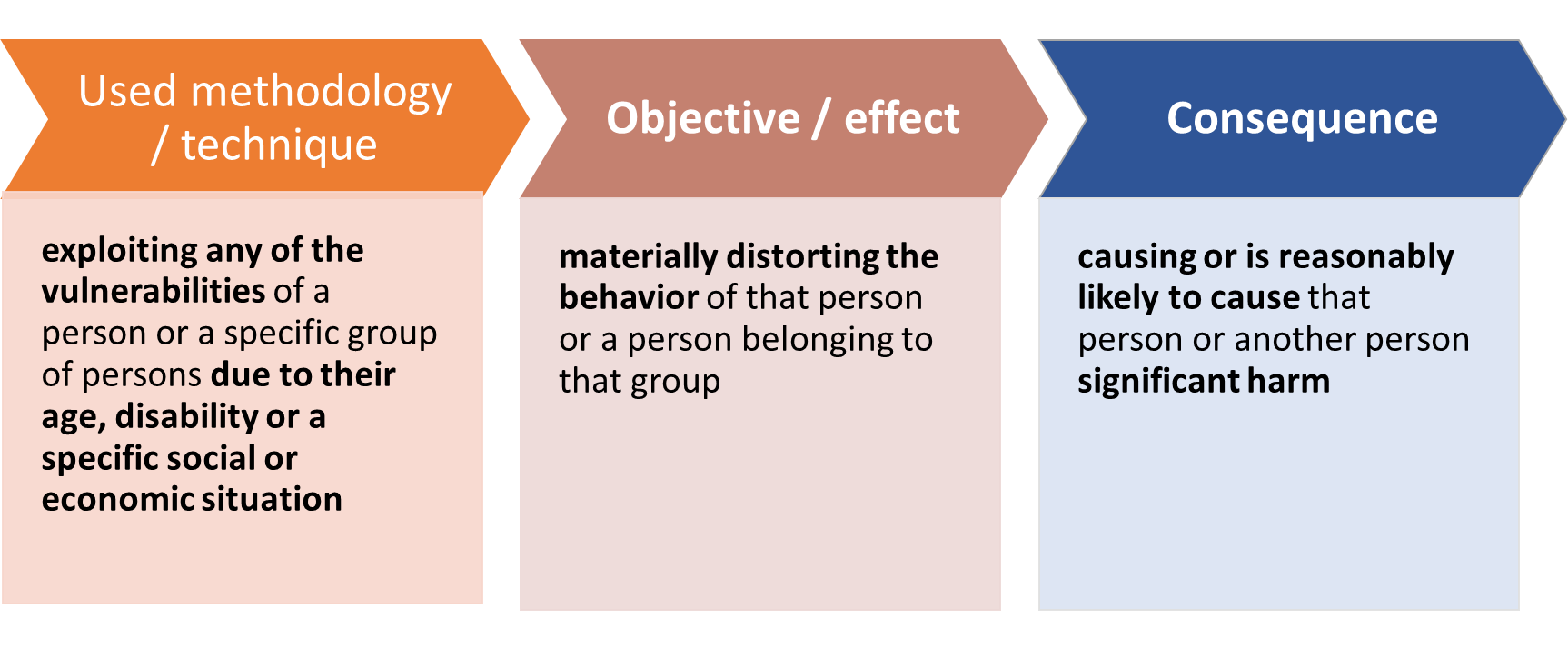

The placing on the market, the putting into service or the use of an AI system that exploits any of the vulnerabilities of a natural person or a specific group of persons due to their

- age,

- disability or

- a specific social or economic situation,

with the objective, or the effect, of materially distorting the behaviour of that person or a person belonging to that group

in a manner that causes or is reasonably likely to cause that person or another person significant harm shall be prohibited.

What vulnerabilities could be exploited under this prohibition?

What vulnerabilities could be exploited under this prohibition?

The text of the AI Act mentions the following vulnerabilities:

- age,

- disability or

- a specific social or economic situation.

The definition of disability is based on Directive 2019/882 on the accessibility requirements for products and services. According to this Directive, '‘persons with disabilities’ means persons who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others (Article 3(1) of Directive 2019/882).

Any vulnerability due to a specific social or economic situation can be understood as vulnerability due to a specific social or economic situation that is likely to make those persons more vulnerable to exploitation, such as persons living in extreme poverty, ethnic or religious minorities (see Recital 29). This third category could, of course, also include a number of other vulnerabilities not explicitly mentioned in the recital to the regulation (some more examples such as political, linguistic or racial minorities, migrants, LGBTIA+ people, etc. can be found here).

The Recital of the AI Act (Recital 29, emphasis added) also makes clear that

[the] prohibitions of manipulative and exploitative practices in this Regulation should not affect lawful practices in the context of medical treatment such as psychological treatment of a mental disease or physical rehabilitation, when those practices are carried out in accordance with the applicable law and medical standards, for example explicit consent of the individuals or their legal representatives.

Of course, the exploitation of vulnerabilities can also be done indirectly, the outcome might be unintentional, it is sufficient if the application of the given AI practice leads to the fact that the vulnerability significantly distorts the behaviour of the affected person or group of persons and they (or other persons) suffer or likely to suffer significant harm.

2.3 Social scoring systems [Art. 5 (1) c)]

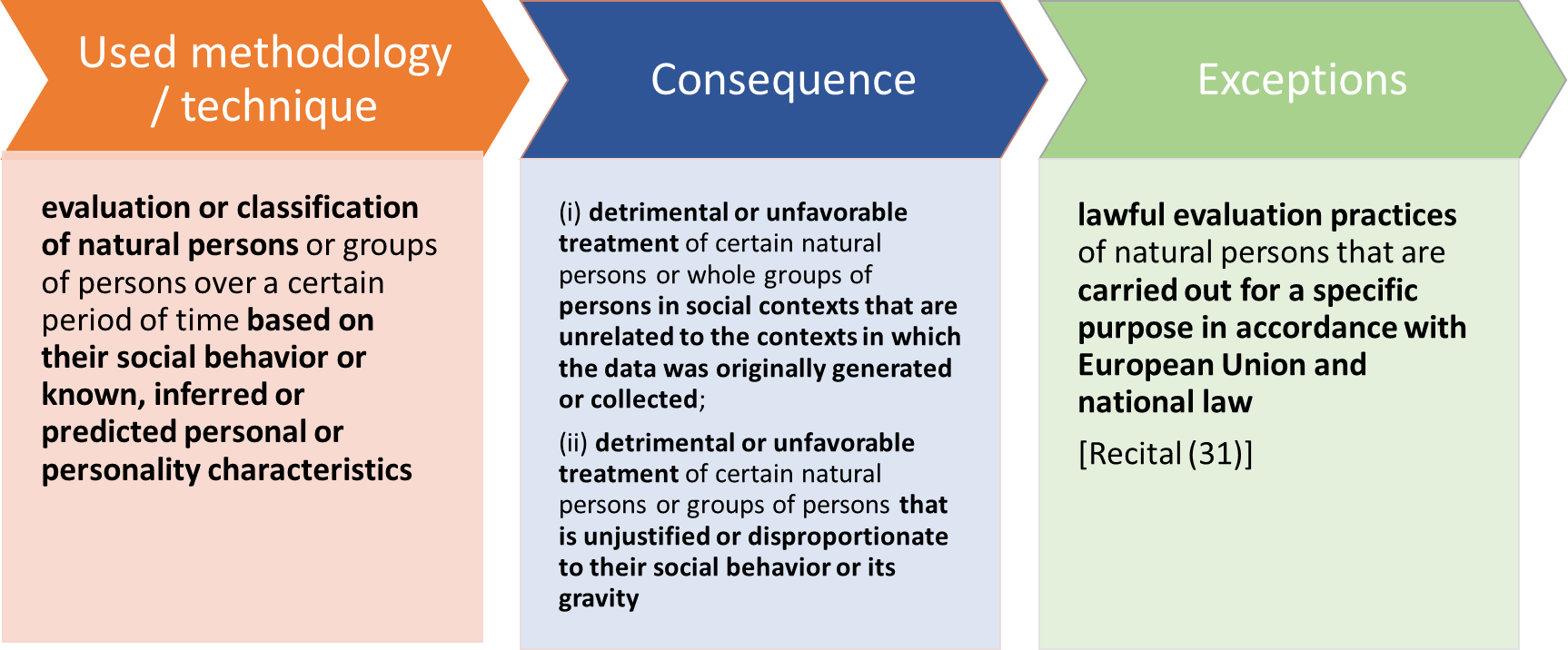

The placing on the market, the putting into service or the use of AI systems for the evaluation or classification of natural persons or groups of persons over a certain period of time based on their social behaviour or known, inferred or predicted personal or personality characteristics,

with the social score leading to either or both of the following:

(i) detrimental or unfavourable treatment of certain natural persons or groups of persons in social contexts that are unrelated to the contexts in which the data was originally generated or collected;

(ii) detrimental or unfavourable treatment of certain natural persons or groups of persons that is unjustified or disproportionate to their social behaviour or its gravity

shall be prohibited.

When it comes to the application of social scoring systems, the example of China is probably the most likely to come to mind, however, in many cases this association is not entirely accurate (more details and analyses on this are available e.g. here, here and here). Perhaps the episode "Nosedive" from the series Black Mirror (2016) may also pop up as a point of reference for many browsing the AI Act.

When it comes to the application of social scoring systems, the example of China is probably the most likely to come to mind, however, in many cases this association is not entirely accurate (more details and analyses on this are available e.g. here, here and here). Perhaps the episode "Nosedive" from the series Black Mirror (2016) may also pop up as a point of reference for many browsing the AI Act.

The aim of the regulation is to prevent discriminatory outcomes and the exclusion of certain group, since such systems "[...] may violate the right to dignity and non-discrimination and the values of equality and justice" (see recital 31 of the AI Act).

Importantly, the prohibition applies either to the use of evaluations outside the context ("in social contexts that are unrelated to the contexts in which the data was originally generated or collected") or to situations where disproportionate or unjustified consequences may be applied in relation to the social behaviour of the persons concerned or to the gravity of such social behaviour.

This prohibition should not affect lawful evaluation practices of natural persons that are carried out for a specific purpose in accordance with Union and national law, e.g. in relation to financial solvency, insurance relationships (e.g. car insurance) and many other areas of life.

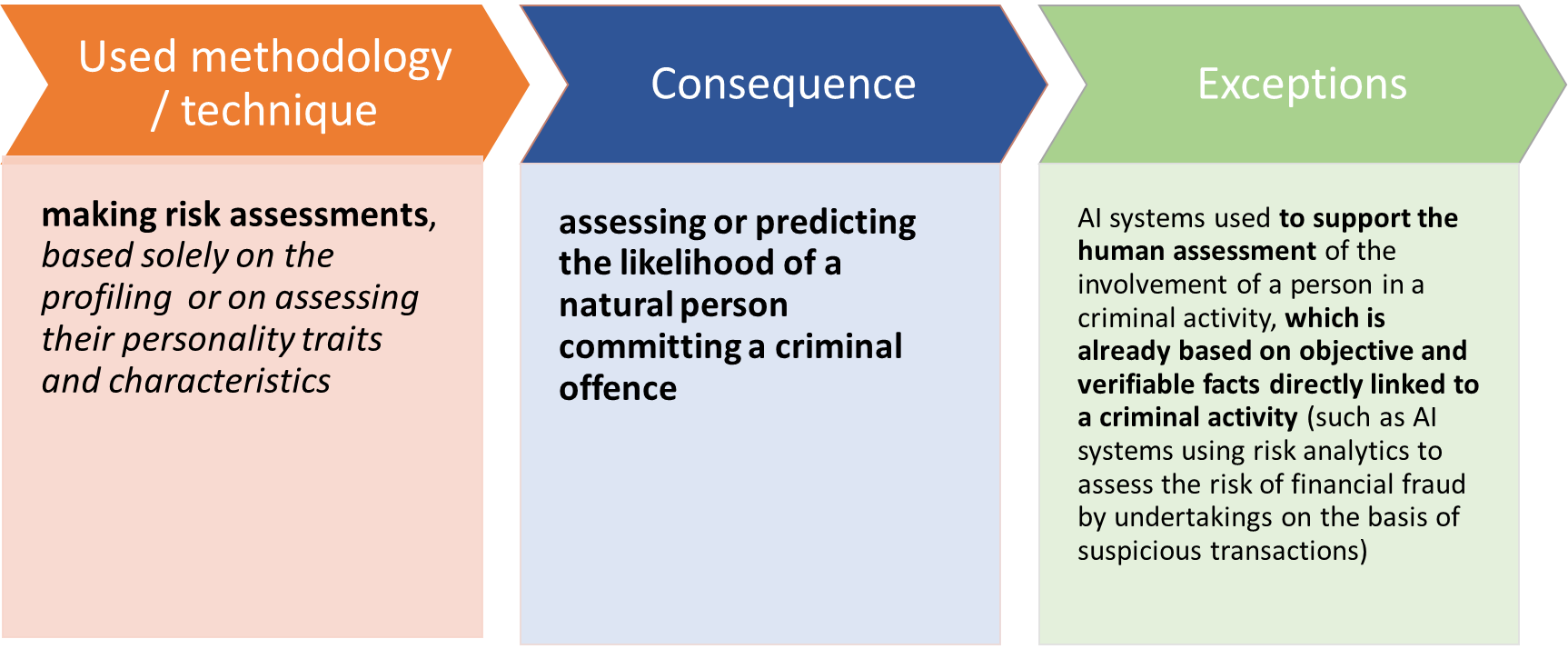

2.4 AI systems intended for risk assessment regarding the likelihood of crime [Art. 5 (1) d)]

The placing on the market, the putting into service for this specific purpose, or the use of an AI system for making risk assessments of natural persons

in order to assess or predict the risk of a natural person committing a criminal offence, based solely on the profiling of a natural person or on assessing their personality traits and characteristics

shall be prohibited.

This prohibition shall not apply to AI systems used to support the human assessment of the involvement of a person in a criminal activity, which is already based on objective and verifiable facts directly linked to a criminal activity.

If we associate to Black Mirror when discussing social scoring systems, then Philip K. Dick's famous short story (1956) and the Steven Spielberg-directed film (2002) "The Minority Report" might be used as an example in connection with crime prediction systems.

In developed legal systems, including of course in the EU, the presumption of innocence is a key principle. In line with this principle, natural persons should always be judged on their actual behaviour and consequently

natural persons should never be judged on AI-predicted behaviour based solely on their profiling, personality traits or characteristics, such as nationality, place of birth, place of residence, number of children, level of debt or type of car, without a reasonable suspicion of that person being involved in a criminal activity based on objective verifiable facts and without human assessment thereof. (see Recital 42, emphasis added)

The AI Act builds on the definition of profiling in data protection regulations, according to which ‘profiling’ means any form of automated processing of personal data consisting of the use of personal data to evaluate certain personal aspects relating to a natural person, in particular to analyse or predict aspects concerning that natural person's performance at work, economic situation, health, personal preferences, interests, reliability, behaviour, location or movements (Art. 3(4) GDPR, Article 3(4) of Directive 2016/680, or Article 3(5) of Regulation 2018/1725).

The use of systems supporting human assessments based on objective assessments in the area of law enforcement is not covered by the prohibition. In this context, special attention must be paid in the future to ensuring that systems genuinely support human decision-making, and that the role of decision making must not be taken over by the AI systems, and it must be ensured that the human involvement is not formal. (For the dangers of using such predicting systems, see, for example, this, this and this article.)

As regards the scope of the prohibition, attention should be paid to the limitation that this prohibition refers to 'putting into service for that specific purpose', i.e. the assessment or prediction of the risk that a natural person commits a criminal offence.

This prohibition does not preclude the application of

risk analytics that are not based on the profiling of individuals or on the personality traits and characteristics of individuals, such as AI systems using risk analytics to assess the likelihood of financial fraud by undertakings on the basis of suspicious transactions or risk analytic tools to predict the likelihood of the localisation of narcotics or illicit goods by customs authorities, for example on the basis of known trafficking routes. (See Recital 42, emphasis added.)

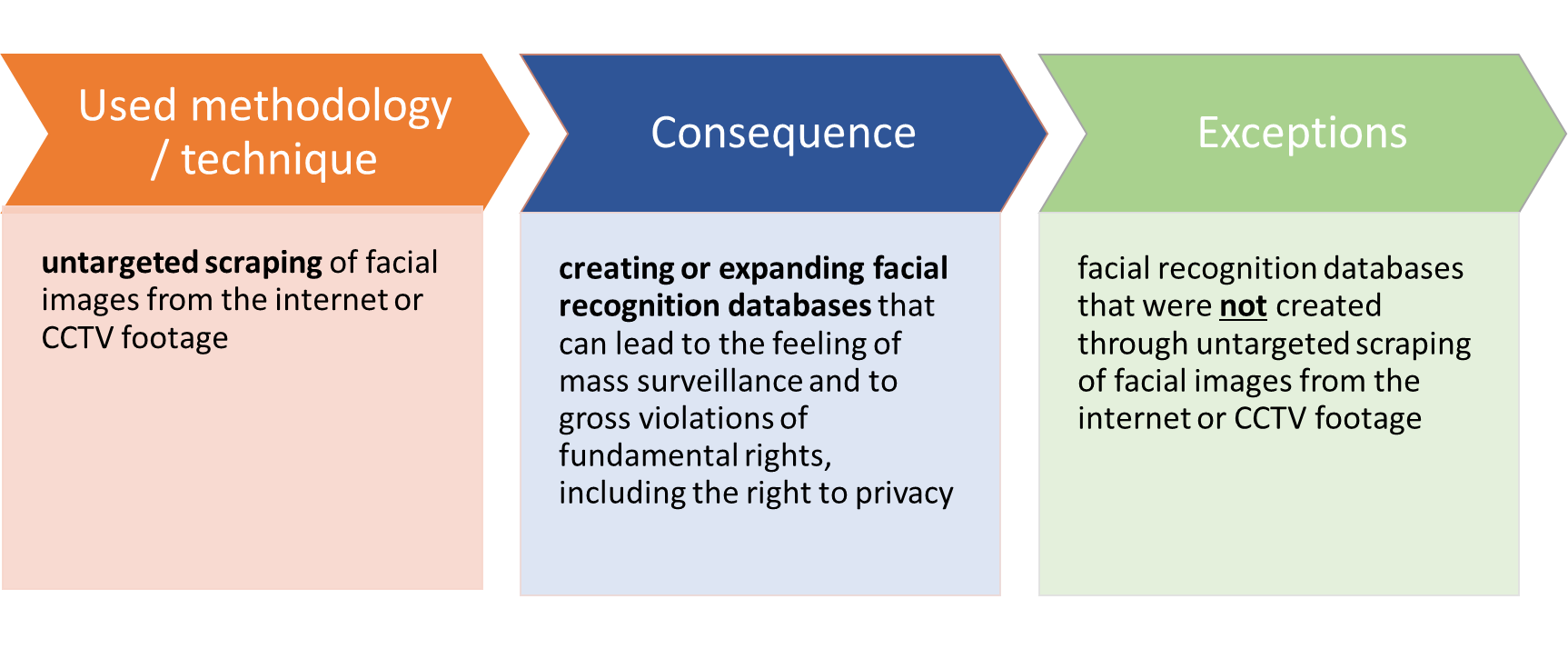

2.5 Facial recognition databases [Art. 5 (1) e)]

The placing on the market, the putting into service for this specific purpose, or use of AI systems that create or expand facial recognition databases through the untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet or CCTV footage shall be prohibited.

The need for a prohibition on the creation and expansion of facial recognition databases through untargeted web scraping can be justified quite easily, since such a service is already available on the market. A company called Clearview AI is essentially doing this, and although regulatory and judicial proceedings have been ongoing against the company for years, it continues to do so (according to a BBC article published in October 2023, Clearview AI has collected about 30 billion images from the internet into their database, and according to news reports, more than 1 million search requests were initiated by the police in the US until 2023).

The need for a prohibition on the creation and expansion of facial recognition databases through untargeted web scraping can be justified quite easily, since such a service is already available on the market. A company called Clearview AI is essentially doing this, and although regulatory and judicial proceedings have been ongoing against the company for years, it continues to do so (according to a BBC article published in October 2023, Clearview AI has collected about 30 billion images from the internet into their database, and according to news reports, more than 1 million search requests were initiated by the police in the US until 2023).

Several data protection authorities in the EU initiated proceedings against Clearview AI (e.g. in France, Greece, Italy) and imposed significant fines. The company also received a fine from ICO (the data protection authority in the UK), but successfully initiated judicial review (it is important to point out, however, that the court ruling was more about procedural issues than about the judicial "approval" of the data collection practices followed by Clearview AI).

The company had problems with the authorities not only in Europe, but worldwide (e.g. in Australia). In the United States, a class action lawsuit was recently settled with an unusual offer: the plaintiffs were offered a stake in the company. Earlier, in 2022, a settlement was already reached in the US in the proceedings against the company. (Please also see this German-language article by Mario Martini and Carolin Kempera that illustrates Clearview AI's practices and the privacy implications.)

In connection with the prohibition of the AI Act, the main question is what "untargeted scraping" means. As defined by the ICO,

web scraping involves the use of automated software to ‘crawl’ web pages, gather, copy and/or extract information from those pages, and store that information (e.g. in a database) for further use. The information can be anything on a website – images, videos, text, contact details, etc.

Recently, data protection authorities have been paying increasing attention to the issue of web scraping and its data protection implications, especially in the context of the development and use of artificial intelligence. Relevant authority opinions and guidelines include, for example:

- ICO´s consultation paper, "Generative AI first call for evidence: The lawful basis for web scraping to train generative AI models",

- Dutch Data Protection Authority´s guidance on web scraping (in Dutch, short summary in English is available here)

- joint statement by several data protection authorities on the subject (signatories include, for example, data protection authorities in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Morocco, Argentina, Canada, Switzerland, Norway, Mexico, Hong Kong, etc.),

- the French Data Protection Authority (CNIL) already issued guidance on web scraping in 2020 (available in French here), but a very recent guidance published on 2 July 2024 - currently under consultation - again addresses this topic in the context of the development of AI models;

- the Italian Data Protection Authority´s (Garante) guidance on the protection of personal data from web scraping (this guidance approaches the issue not from the point of view of web scrapers, but from the point of view of the obligations of controllers who own a website and process personal data through it; the full document is available only in Italian).

(A good summary on the topic, which also covers practice and court proceedings in the USA, is Müge Fazlioglu´s "Training AI on personal data scraped from the web", IAPP, November 2023, and a recent summary of data protection developments in the EU, from Ádám Liber and Tamás Bereczki: "The state of web scraping in the EU", IAPP, 2024.)

On the other hand, it can be seen that companies developing AI are interested in having as much data as possible that is necessary for the development of their models, and where appropriate, they offer services that serve to inform about the available information and prepare summaries. Companies developing AI or providing AI-based services often do not shy away from circumventing or bypassing the safeguards applied by content providers and website operators in order to collect the data they need. In Australia, it has just recently attracted a lot of attention that databases used to develop AI models also include a large number of images obtained through unlawful non-targeted scraping from the web.

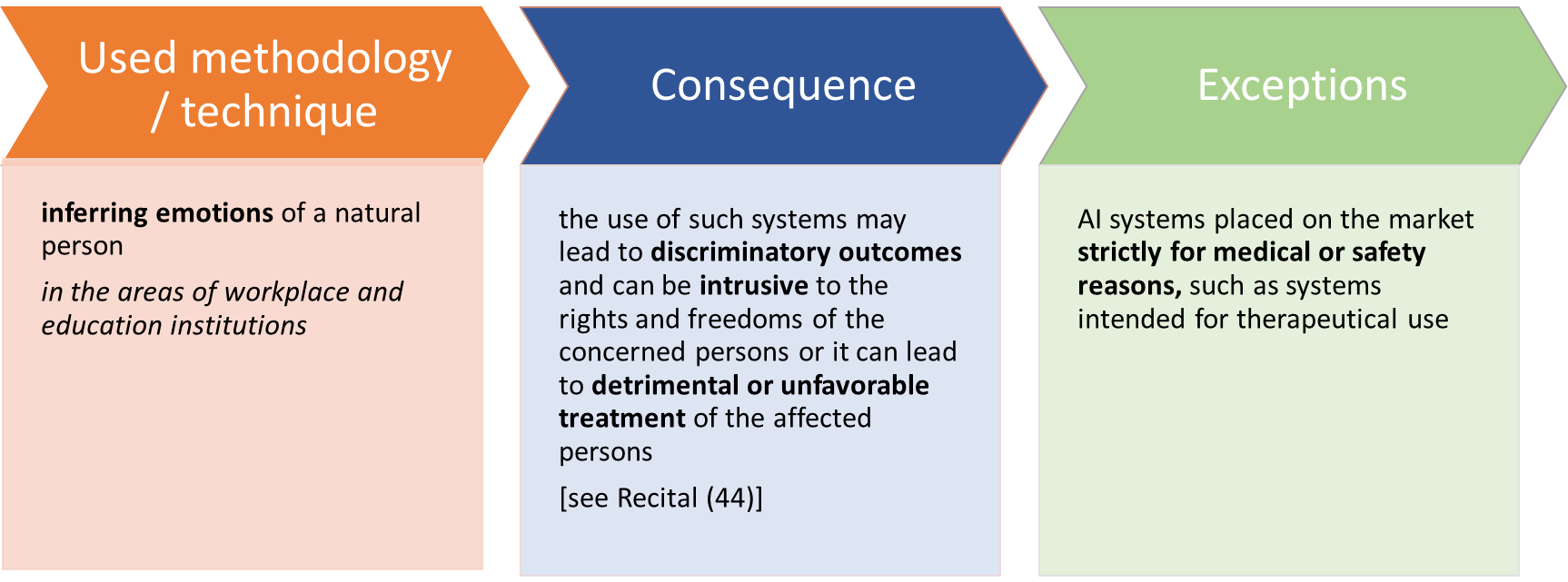

2.6 Emotion recognition in the areas of workplace and education institutions [Art. 5 (1) f)]

The placing on the market, the putting into service for this specific purpose, or the use of AI systems to infer emotions of a natural person in the areas of workplace and education institutions shall be prohibited,

except where the use of the AI system is intended to be put in place or into the market for medical or safety reasons.

The reason for the partial prohibition on emotion recognition systems stems from the

[...] serious concerns about the scientific basis of AI systems aiming to identify or infer emotions, particularly as expression of emotions vary considerably across cultures and situations, and even within a single individual. Among the key shortcomings of suchsystems are the limited reliability, the lack of specificity and the limited generalisability." (See Recital 44)

The AI Act defines an emotion recognition system as "an AI system for the purpose of identifying or inferring emotions or intentions of natural persons on the basis of their biometric data" (AI Act, Art. 3, Point 39). What do we mean by emotion under the AI Act? Based on the AI Act (see Recital 18, emphasis added):

The notion refers to emotions or intentions such as happiness, sadness, anger, surprise, disgust, embarrassment, excitement, shame, contempt, satisfaction and amusement. It does not include physical states, such as pain or fatigue, including, for example, systems used in detecting the state of fatigue of professional pilots or drivers for the purpose of preventing accidents. This does also not include the mere detection of readily apparent expressions, gestures or movements, unless they are used for identifying or inferring emotions. Those expressions can be basic facial expressions, such as a frown or a smile, or gestures such as the movement of hands, arms or head, or characteristics of a person’s voice, such as a raised voice or whispering.

The best-known figure in the research of emotion recognition based on facial expressions is Paul Ekman, who began his research in this field in the 1950s. According to his hypothesis, there are universal facial expressions that reflect the same emotions across cultures. During his research, he developed the so-called Facial Action Coding System (FACS). Ekman's theory and system have been criticized extensively, and debates continue to revolve around the possibilities and limitations of emotion recognition. (Ekman's research also inspired a series of films called "Lie to Me", in which the main character starred by Tim Roth excelled at recognizing emotions from facial expressions.)

AI has arrived in this area of controversy, the application of which in emotion recognition also provokes sharp debates and criticisms (see, for example, here and here). For relevant research, it is worth reviewing: Khare et al., "Emotion recognition and artificial intelligence: A systematic review (2014-2023) and research recommendations", Information Fusion, Elsevier, Volume 102, February 2024; and Guo et. al "Development and application of emotion recognition technology — a systematic literature review", BMC Psychol, Feb 24, 2024; 12(1):95.

The main concern, according to the recital to the AI Act, is that systems for recognizing or inferencing emotions may lead to discriminatory outcomes and can be intrusive to the rights and freedoms of the concerned persons. Nevertheless, the AI Act does not establish a general prohibition, but focuses on situations where there is generally an unbalance of power, such as at workplaces and in educational institutions. However, even in this context, exceptions to the prohibition may be possible for medical reasons (e.g. AI systems for therapeutic use) or safety.

Emotion recognition systems, at least those that do not fall within the scope of prohibited AI practices, are high-risk AI systems (see Annex III to the AI Act) and are also subject to information obligations (Article 50(3) of the AI Act).

Meanwhile, it's a huge business, which according to some estimates could generate nearly $100 billion in revenue by 2030. There are many areas of use, from driving a car, through helping people with autism to social interaction, to examining consumer habits. (For some examples of possible use cases, see Rosalie Waelen, "Philosophical Lessons for Emotion Recognition Technology", Minds & Machines 34, 3 (2024), Introduction)

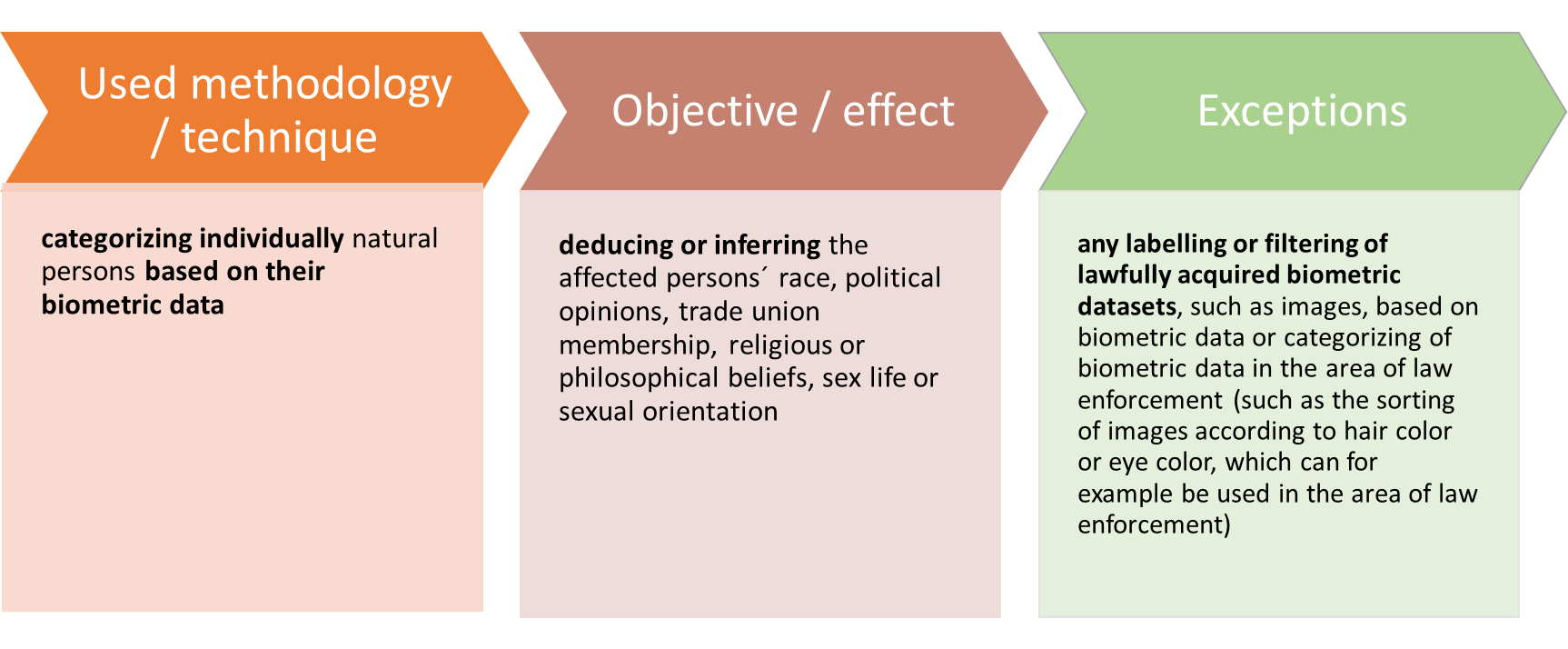

2.7 Biometric categorisation systems [Art. 5 (1) g)]

Biometric categorisation systems that categorise individually natural persons based on their biometric data to deduce or infer their race, political opinions, trade union membership, religious or philosophical beliefs, sex life or sexual orientation shall be prohibited.

This prohibition does not cover any labelling or filtering of lawfully acquired biometric datasets, such as images, based on biometric data or categorizing of biometric data in the area of law enforcement.

According to the AI Act, a biometric categorisation system means "an AI system for the purpose of assigning natural persons to specific categories on the basis of their biometric data, unless it is ancillary to another commercial service and strictly necessary for objective technical reasons."(Art. 3, Point 40 of the AI Act)

The concept of biometric data should be understood in line with the definition in data protection laws, i.e. "biometric data means personal data resulting from specific technical processing relating to the physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics of a natural person, such as facial images or dactyloscopic data" (See Art. 3 (34) of the AI Act, for the defitions in data protection laws, see Art. 4(14) GDPR, Art. 3(18) of Regulation 2018/1725 and Article 3(13) of Directive 2016/680.)

The AI Act provides for exceptions to the prohibition on the use of biometric categorisation systems and examples of this can be found in the recital to the AI Act (see recital 30, emphasis added):

That prohibition should not cover the lawful labelling, filtering or categorisation of biometric data sets acquired in line with Union or national law according to biometric data, such as the sorting of images according to hair colour or eye colour, which can for example be used in the area of law enforcement.

It is important, however, that since biometric data belong to special categories of personal data, if biometric categorisation systems are not prohibited, they qualify as high-risk AI systems (see Annex III of the AI Act). They are also subject to transparency obligations under the AI Act, if these systems are not prohibited (Article 50(3) of the AI Act).

The AI Act also defines law enforcement, which means "activities carried out by law enforcement authorities or on their behalf for the prevention, investigation, detection or prosecution of criminal offences or the execution of criminal penalties, including safeguarding against and preventing threats to public security" (see Article 3, Point 46).

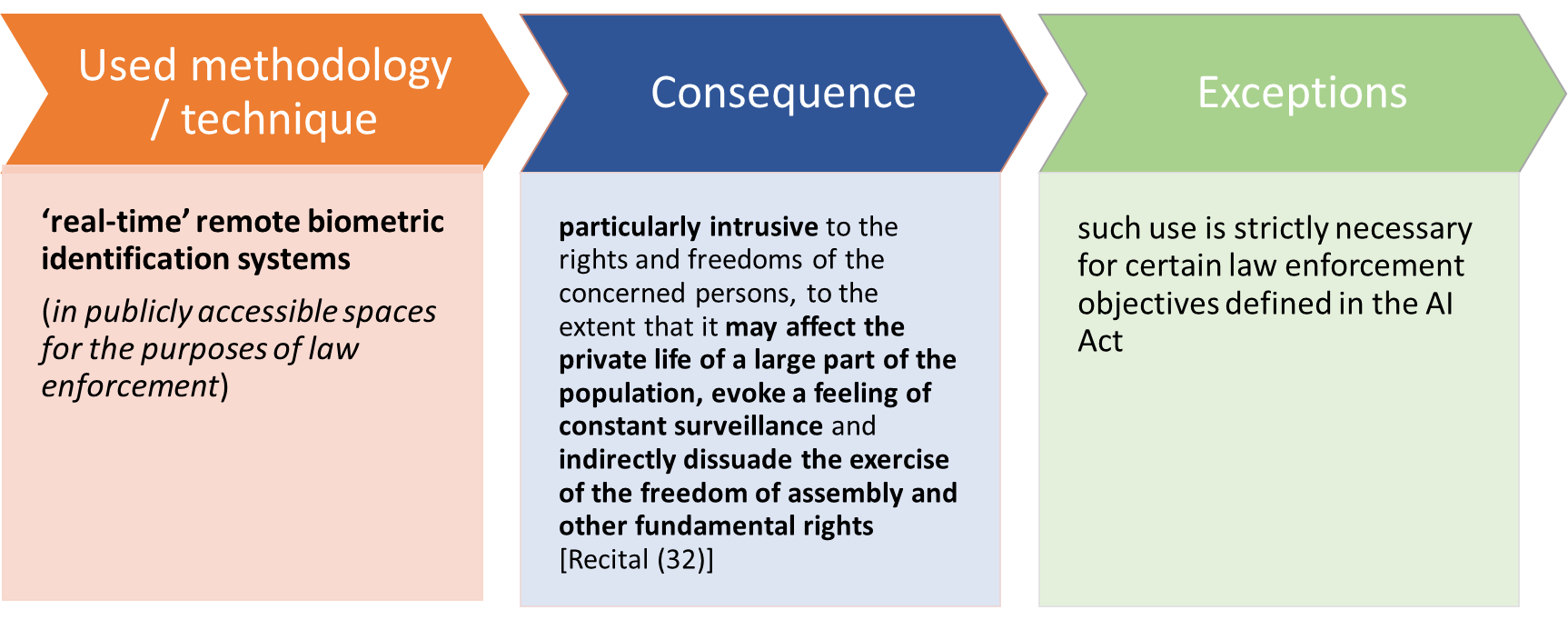

2.8 ‘Real-time’ remote biometric identification systems in publicly accessible spaces for the purposes of law enforcement [Art. 5 (1) h)]

The use of ‘real-time’ remote biometric identification systems in publicly accessible spaces for the purposes of law enforcement shall be prohibited,

unless and in so far as such use is strictly necessary for one of the following objectives:

- the targeted search for specific victims of abduction, trafficking in human beings or sexual exploitation of human beings, as well as the search for missing persons;

- the prevention of a specific, substantial and imminent threat to the life or physical safety of natural persons or a genuine and present or genuine and foreseeable threat of a terrorist attack;

- the localisation or identification of a person suspected of having committed a criminal offence, for the purpose of conducting a criminal investigation or prosecution or executing a criminal penalty for offences referred to in Annex II and punishable in the Member State concerned by a custodial sentence or a detention order for a maximum period of at least four years.

In defining the extent of this prohibition, we must first of all clarify the related notions. According to the AI Act (see Art. 3, Points 35 and 41 to 43):

- biometric identification means the automated recognition of physical, physiological, behavioural, or psychological human features for the purpose of establishing the identity of a natural person by comparing biometric data of that individual to biometric data of individuals stored in a database;

- remote biometric identification system means an AI system for the purpose of identifying natural persons, without their active involvement, typically at a distance through the comparison of a person’s biometric data with the biometric data contained in a reference database;

- real-time remote biometric identification system means a remote biometric identification system, whereby the capturing of biometric data, the comparison and the identification all occur without a significant delay, comprising not only instant identification, but also limited short delays in order to avoid circumvention;

- post remote biometric identification system means a remote biometric identification system other than a real-time remote biometric identification system.

Given that the prohibition applies to the use of such systems in publicly accessible spaces, it is also important to clarify what may be regarded as such places. According to the AI Act, publicly accessible space means "any publicly or privately owned physical place accessible to an undetermined number of natural persons, regardless of whether certain conditions for access may apply, and regardless of the potential capacity restrictions" (see Art. 3, Point 44). The recital to the AI Act also provides more detailed guidance on the interpretation of the concept of publicly accessible spaces (see recital 19, emphasis added):

For the purposes of this Regulation the notion of ‘publicly accessible space’ should be understood as referring to any physical space that is accessible to an undetermined number of natural persons, and irrespective of whether the space in question is privately or publicly owned, irrespective of the activity for which the space may be used, such as for commerce, for example, shops, restaurants, cafés; for services, for example, banks, professional activities, hospitality; for sport, for example, swimming pools, gyms, stadiums; for transport, for example, bus, metro and railway stations, airports, means of

transport; for entertainment, for example, cinemas, theatres, museums, concert and conference halls; or for leisure or otherwise, for example, public roads and squares, parks, forests, playgrounds. A space should also be classified as being publicly accessible if, regardless of potential capacity or security restrictions, access is subject to certain predetermined conditions which can be fulfilled by an undetermined number of persons, such as the purchase of a ticket or title of transport, prior registration or having a certain age. In contrast, a space should not be considered to be publicly accessible if access is limited to specific and defined natural persons through either Union or national law directly related to public safety or security or through the clear manifestation of will by the person having the relevant authority over the space. The factual possibility of access alone, such as an unlocked door or an open gate in a fence, does not imply that the space is publicly accessible in the presence of indications or circumstances suggesting the contrary, such as. signs prohibiting or restricting access. Company and factory premises, as well as offices and workplaces that are intended to be accessed only by relevant employees and service providers, are spaces that are not publicly accessible. Publicly accessible spaces should not include prisons or border control. Some other spaces may comprise both publicly accessible and non-publicly accessible spaces, such as the hallway of a private residential building necessary to access a doctor's office or an airport. Online spaces are not covered, as they are not physical spaces. Whether a given space is accessible to the public should however be determined on a case-by-case basis, having regard to the specificities of the individual situation at hand.

Other posts in the "Deep Dive into the AI Act" series: